From Gladiators to MOOCs: Higher Education, Technology, and Social Mobility

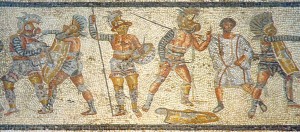

I ask my students, “If you were a gladiator, which technology would you prefer: a trident, a net, or a wooden sword?” It is a question I would like you to consider; a question to which I will return.

Even before Verus and Priscus entered the Coliseum in AD 80, individuals realized that access to higher education combined with appropriate technologies was a pathway to social mobility. Although we often think of gladiators as slaves and criminals, many poor freemen chose to train to become gladiators. These men made the decision to enter a gladiatorial school because they considered obtaining a higher education as their best opportunity for social mobility.

Even though having the best technologies for fighting were important in the arena, an understanding of the liberal arts was equally important for success. For example, gladiators and those who trained them needed to understand theatre. Gladiatorial costumes were carefully chosen to represent the armor of Rome’s enemies; not Romans. Furthermore, the emperor and other spectators wanted good entertainment. In addition to courage, good theatre and knowing how to please your audience could prevent your death even if you were defeated by your opponent.

When the Chinese Imperial Exams were introduced in the sixth century, their purpose was to establish a meritocracy for public service. By the end of the fourteenth century, the Chinese Imperial Exams included testing knowledge of the Confusion classics as well as calligraphy and the ability to compose poetry. Having a good brush was a required technology for passing these exams.

For Samurai warriors in feudal Japan, knowledge of the katana—or Samurai sword—might bring success on the battlefield, but it would not lead to social advancement without an understanding of social etiquette. Miyamoto Musashi’s c. 1645 classic, The Book of Five Rings, details the need of a liberal arts education for a Samurai to obtain the social mobility that could result from his higher education training.

The value of social etiquette over military knowledge can be seen when the warrior left his katana outside before participating in the tea ceremony. In fact, the building in which the tea ceremony was held was constructed in such a way that it was not possible to enter it in full military costume.

Social mobility through higher education was also important for African slaves in Barbados where the definition of skilled vs. unskilled slave labor was a matter of social hierarchy as well as in the difficulty of learning or performing a task. Gaining higher education to learn carpentry or some other skilled trade did not guarantee social mobility if the individual could not navigate the social nuances of plantation life as well as the socio-political and cultural forces that governed the island. Without the skills currently learned by students of anthropology, psychology, rhetoric, and other liberal arts disciplines, learning a skilled trade through higher education did not even guarantee the ability to stay alive.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, education systems in Western Europe and the Americas were greatly impacted by enlightenment thinking. Eventually, education was not limited to the social elite and higher education became available as a path for social mobility. However, Henry Ford and the other industrialists—including too many business and political leaders in the 21st century—did not necessarily see a need for a liberal arts curriculum. Citizens educated in the liberal arts in addition to the technologies of their skilled trades are more apt to demand better working conditions or other measures that threaten established social hierarchy. Why risk unions or reform movements if you can keep your workforce ignorant of the liberal arts and the critical thinking skills that come with such an education?

When I was first approached about developing an on-line course at Kirtland Community College, I declared that students could not learn effectively in an on-line environment. In response, I was essentially told that I was being ignorant because I had not even investigated on-line technologies. After investigation, I was one of the first three Kirtland professors to offer an on-line course.

In my initial response to on-line education, I made the mistake that most of my students make when I ask them if they would prefer a trident, a net, or a wooden sword. I focused on the technology itself without considering context.

Typically, when queried about their technology of choice, students immediately dismiss the value of the wooden sword and debate whether or not the trident or net would be preferred. Yet, the wooden sword is a far more valuable technology than either the trident or net.

The poet Marcus Valerius Martialis describes the dramatic confrontation between Verus and Priscus when both fought valiantly and both simultaneously raised their finger in defeat. Because he was so impressed with their skills, Martialis explains “Misit utrique rudes et palmas Caesar utrique: hoc pretium uirtus ingeniosa tulit;” that the Emperor Titus “sent wooden swords to both and palms to both: Thus skillful courage received its prize.” By sending them wooden swords, Titus gave Verus and Pricus their freedom.

Last week, when I posed the trident/net/sword question to one of my classes, the students surprised me by asking a series of questions. “What type of fight is taking place?” “What weapon does my opponent have?” “Am I fighting another gladiator or an animal?” Instead of instantly debating the technology, the students wanted to know the context in which the technology was being used.

Context is the key criteria when discussing MOOCs and other education technologies. For example, a brush does not appear to be an impressive technology. But given the choice between a brush and a computer, the best technology for writing your Chinese Imperial Exam is the brush because you cannot produce quality calligraphy with a computer.

Unless we learn to ask the right questions about context when we approach developing technologies, we could end up choosing a trident or a net over our freedom.

- –Steven L. Berg, PhD

Photo Caption: Zliten mosaic, c. 200.

I find the MOOC courses to be ideal for a senior citizen who has no need for credit courses, who wants to learn certain skills and/or content and who does not want to go to a class or activity at a set time (context). So I am taking three Coursera courses on subjects that range from cinema to search for other earths to soul from a materialistic point-of-view.