Speaking of Failure

In “The Invention of Failure,” Dr. Cathy N. Davidson rightly argues that we should eliminate “flunk out” courses which have traditionally been defined as rigorous and demanding simply because so many students fail them. Instead, she proposes developing rigorous and demanding courses that set a high bar of excellence and in which all students could theoretically earn an “A.”

In “The Invention of Failure,” Dr. Cathy N. Davidson rightly argues that we should eliminate “flunk out” courses which have traditionally been defined as rigorous and demanding simply because so many students fail them. Instead, she proposes developing rigorous and demanding courses that set a high bar of excellence and in which all students could theoretically earn an “A.”

I share Davidson’s fascination the “failure in the Industrial Age, and the clear relationship between learning failure and Taylorism and all the aspect of scientific labor management of the era.” However, while studying the invention of failure and its legacy, we need to also address the fear of failure that millennial students bring to the classroom.

Today’s younger students have too often been raised in environments that are overly protective. They have experienced competitive sports in which no score is kept and events where everyone gets a trophy for simply showing up. These students have lived with helicopter parents who solve difficulties for their children instead of letting their children grow into adulthood by learning from their mistakes. Unfortunately, some of these “children” are already their 20s.

Rigorous standards can be threatening to students whom have not been permitted to experience failure. As a student once told my Dean, “I don’t want to think. I want Dr. Berg to tell me what he wants.” This was a bright student who could have easily met the expectations of the course, but she was too afraid of failure to even risk starting out on the path to success.

Some of the strategies I have been incorporating in my syllabi to address the fear of failure include:

Participation = 70%

If students attend class regularly and do their homework, they are essentially guaranteed a “C” in the course. I explain to students that those who attend class regularly and complete assignments cannot help but get an even higher grade than a “C” and that many (most?) of the class can earn 4.0s.

While the guaranteed 70% is comforting to students who fear failure, high expectations mean that students cannot get a trophy by simply showing up for class. Students must be present and prepared. For example, students who don’t complete the required research for tomorrow’s class will be permitted to participate in the discussion, but they will not earn any participation points.

Ruth Jeffrey’s “ was a homework assignment for which she earned participation points. Statistically, this assignment was worth about 5% of the course grade, but to include such assignments as part of participation makes them less threatening to those students who fear failure.

False Rubrics

Because I do not assign topics and instead insist that student projects grow out of broad based research, students can fear failure because they are not handed a rubric defining the specifics of their lightning talks or other major assignments. To help allay their fears, I give students a list of the 14 types of references they will be consulting. It looks like a rubric and fearful students find comfort in being able to check off each step as it is completed.

I refer to this as a false rubric because it provides comfort without providing the specific details the fearful students want; details that would get in the way of quality research.

Small Steps

The first research assignment is for students to look up their broad topic (e.g. the Civil War or contemporary education) in Wikipedia and to do an Internet search concerning their topic. Because Wikipedia and Google are familiar to them, students do not experience a fear of failure. By the time they are asked to consult sources not written in English, they already have a series of successfully completed assignments and have less fear when asked to do the seemingly impossible.

Teaching Previous Student Work

Last year, I launched three websites on which to publish quality student work: College History, Film Studies, and Scholarly Voices. This semester, I have already assigned essays written by previous students to my current students whose first day of class was last week. By assigning the work of previous students such as Brandon Schulz’s “,” current students are able to see the results of a process that they do not yet comprehend. They also learn why some Civil War soldiers glowed in the dark.

Focus on Revision

Even if they totally bomb an assignment, I assure students that the worst case scenario is that I will help them develop the skills they need to successfully revise the assignment into a successful project. The focus on revision not only lessens the fear of failure but it also supports the concepts of continuous improvement and building on success.

Ironically…

Ironically, as I have taken steps to lessen students’ fear of failure, I have actually raised the expectations and rigor of the courses I teach. By breaking the research process into even smaller steps, I require more research than I have previously expected when I taught processes in larger chunks.

Some Students Still Fail

Even when classes are designed for success, some students will choose failure over engagement. Others will have events from their personal lives take an unrecoverable toll on their academic lives. Others will make bad decisions that lead to failure and (hopefully) future learning. But, as Davidson argues, we should not design our courses in such a way that guarantee that a certain percentage of our students will fail. Instead, we need to design rigorous courses in which all students could theoretically succeed.

- –Steven L. Berg, PhD

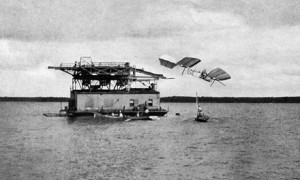

Photo Caption: First failure of the manned Aerodrome, Potomac River, 7 October 1903.

LEAVE A COMMENT