Political Transparency in the Classroom

Please note: There is some language in this essay that some could find offensive; language that usually does not appear in one of my essays.

Too many years ago to remember the source, I read an article by a political science professor who was proud of the fact that, at the end of the semester, his students were unaware of his political views. I remember thinking, “How sad.”

Too many years ago to remember the source, I read an article by a political science professor who was proud of the fact that, at the end of the semester, his students were unaware of his political views. I remember thinking, “How sad.”

As someone who has been involved in politics since he was in seventh grade, I have many stories to tell about campaigning for various candidates, working for a Member of Congress and a State Senator, managing millage elections, and being on the ballot myself. If I taught political science, it would be a shame if I could not share these experiences with students because doing so would allow them to know my political views.

In our current political climate, sharing personal views is fraught with peril. For example, I screen Immersion (2009) about a Mexican-born boy attending a school where teachers are forbidden to speak Spanish to their students. Students in 2017 could too easily jump to the incorrect conclusion that the film concerns the Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and that I am showing it to advocate against President Trump’s immigration policy. Immersion was not written about DACA which did not begin accepting applicants until five years after the film was released. But, as a professor, I need to be aware of the lens through which students might view the film.

Arguably, the safest approach might be to take the position of the political science professor and not mention our political views in class. However, even such a seemingly safe approach is doomed to failure. Simply assigning a reading or selecting a topic for discussion might be viewed as advocating our personal positions. For example, a student once complained that I was trying to force my religious views onto the class because I taught a lesson on Muhammad Iqbal who was the intellectual founder of Pakistan. Even after being informed that I am not a Muslim, the student persisted in her complaint.

So what, then, is the solution? While there is not, unfortunately, an easy answer to this question, transparency has generally worked for me.

From the beginning of the semester, I explain—and often repeat—that “While Steve Berg might care passionately about your political views, Dr. Berg doesn’t give a damn.” Because I am not prone to swearing in the classroom, the mild profanity adds to the impact of the statement which I follow up with specific examples. Sometimes, I tell the story of a former student who advocated that homosexuality is sinful. I explain that I disagreed with the student’s analysis not because I am gay but because I prefer reading scripture—or any text—in its socio-historical context. The student took a more literal approach to scripture. His approach is valid and he earned a 4.0 in a class in which he argued that his professor was going to Hell.

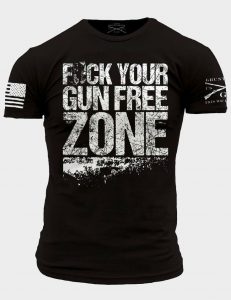

Sometimes, with their permission, I will engage with a current student to make the same point. For example, this semester a student1 wore a t-shirt to class that read “Fuck Your Gun Free Zones.” Not only did I find the shirt offensive, but I disagreed with the message. During class, the student—at my request—stood and showed his t-shirt to his colleagues. He stated his views on gun free zones and I argued why I thought that schools should be gun free. After our exchange, I provided a detailed explanation as to how I would help this student write the best essay possible arguing against gun free zones because Dr. Berg only cares about how well the student writes; not the student’s point of view on the topic.

This does not mean that all points of view have equal merit in my classroom. We distinguish between educated an uneducated opinions. For example, I once upset a student by asking him to provide evidence to support his argument during a class discussion. His response was that he had a right to his opinions. “While that it true,” I replied, “in this class you must provide evidence.” He decided to drop the course.

Because my student who wants to “Fuck Your Gun Free Zones” can support his position with evidence, he has no fear of failing the course because Steve Berg neither approves of the word “fuck” nor supports his political position. It is Dr. Berg whom this student has to please and he pleases Dr. Berg with solid research. While I might suggest that “fuck” is not an appropriate word for an academic paper, I would not be surprised if this student comes up with a well-reasoned argument that such a word was appropriate for his essay; an argument that will allow him to both use the word and earn a 4.0.

- –Steven L. Berg, PhD

1Because he is a current student who could be identified as the individual mentioned in this essay, I received this student's permission to cite this example. He also told me that I was welcome to use his name, but I have chosen not to do so.

LEAVE A COMMENT