Learning in a New and Unconventional Way Is Scary

When pressed by students to come up with a research topic because they cannot think of a topic on their own, I have been known to suggest that they write about the benefits of meditating in charnel grounds and to begin their research by reading the Satipatthana Sutta. As I begin to explain that the various states of decomposition are important to consider, students suddenly become motivated to come up with a topic more in line with their own interests.

When pressed by students to come up with a research topic because they cannot think of a topic on their own, I have been known to suggest that they write about the benefits of meditating in charnel grounds and to begin their research by reading the Satipatthana Sutta. As I begin to explain that the various states of decomposition are important to consider, students suddenly become motivated to come up with a topic more in line with their own interests.

Tory Rogers gives us insight into why students appear reluctant to pursue their own interests: “Learning in a new and unconventional way is a scary idea to most students. It means straying away from the norm of the traditional college lecture; knowing more than just book material.” In order to comfortably move to the new and unconventional, students must trust their professors.

Charlotte Clapham observes that “there is definitely a link between distrusting our professors and our ready access to global information” because we can now easily see corruption in all forms of authority. Jesse Peabody traces this distrust back to the American Revolution when “we didn’t agree with the authority figure so we got that anti-authority attitude.” Tanaja Campbell asks “how can I trust a professor when he or she never even learns my name?” Campbell goes on to explain that when a professor doesn’t know her name “it makes me feel as if I’m just another seat filler contributing to their paycheck, rather than their student.”

Alene Archie articulates a common concern held by many students, “There’s no sense of enlightenment or giving me experience outside of using a pen and paper [in the traditional classroom]. Physics, Trigonometry, and Chemistry are not used outside of the school building in my everyday life.” Annastasia Guzik agrees “that students don’t truly care about the topic that a teacher is talking about unless it ‘deals’ with what they think they’re in school for.” Joking that even a little understanding of physics can keep people from making an appearance on World’s Dumbest is not really a convincing argument for studying physics.

But how do we help students appreciate the connections between academics and their lives? After stating “Let’s be realistic, how many people in a physics class will have this information fully retained?” Team Slaughterhouse argues, “This is why student interaction is necessary.” They continue “students can help others comprehend in a different light” and that student-to-student interaction can supplement the traditional lecture. They conclude their argument by observing that “collaborating with colleagues helps us individually become more creative.”

Student can meaningfully collaborate and make real contributions within an individual classroom and by participating in discussions that take place at HASTAC, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed, and other venues. Suzanne Hakim addresses the importance of public collaboration; “Never in my academic career have [I] been able to connect and share thoughts and opinions with my peers and multiple professors on an intellectual level. This is so refreshing … knowing that we do matter, we aren’t just a ‘class or group’ we are individuals with independent thoughts.”

Collaboration in the real world can have its dark side; something Leslie Nirro learned when she was called an “idiot” by an individual who commented on “Breaking Down Barriers Between the Humanities and Sciences.” But learning to deal with trolls, controversy, and criticism are educationally important. My students have their favorite borderline troll whom they refer to as “our friend [name redacted]” and from whom they have learned how to be better commentators and collaborators even though our friend has yet to learn those same skills.

For students to feel confident expressing their thoughts and opinions, they need to trust that their professors truly want to hear their opinions. Being called an “idiot” by a troll is hurtful but it does not impact a student’s grade. Before encouraging students to express their opinions, we need to communicate to them that we are prepared to have our own thinking challenged. For example, in “Nanook of the North: Inventions Toward Racism,” Zachary Marano wrote that “I question the limitation of analyzing just short films.” He then proceeds to develop a cogent argument as to why his professor gave a flawed assignment.

Within the next week, another student will be publishing a well-written comment to a HASTAC posting; a comment in which he is taking a political position with which I strongly disagree. I have seen the comment only because the student asked me to read it prior to publication so he could receive confirmation that his criticisms did not take on the tone of our friend the borderline troll. Whether or not I agree with his position is not a concern.

Although it might be easier for me to simply assign students to do research on the Satipatthana Sutta, Jimmy F. Bloink Furniture, or other topics that interest me, more learning comes from engaging students in discussion about subjects meaningful to them. A student limited only to my interests can not do their best work. “The College Experience: A Modern Day Paddy West?” is so successful because it is inspired by Andrew Shaw’s interests; not his professors.

Although some students will not take advantage of the opportunities we offer them to become more involved in their educations, those students are no worse off than if we had not provided the opportunity. But if we don’t provide opportunities, we do a disservice to the majority of our students who want to make meaningful connections between their academics and their personal lives.

- –Steven L. Berg, PhD

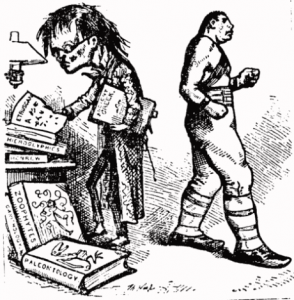

Photo Caption: Thomas Nast dealt with the issue of not trusting educational pursuits in this 1875 editorial cartoon.

LEAVE A COMMENT